Commentary: Martin Luther King, Jr. and hope, half a century later

Andrea Currie

News Editor

“Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred,” says the speaker. Someone shouts, “Amen!” and the crowd swells with applause and cheers.

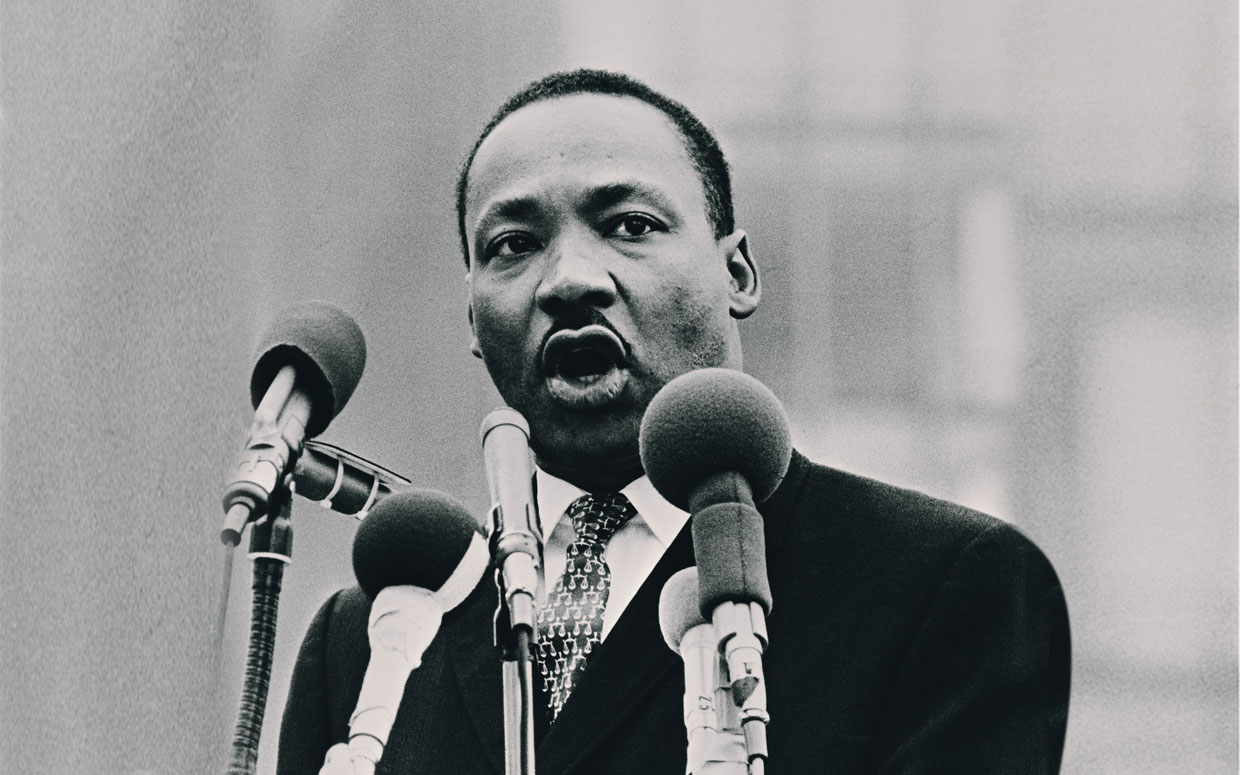

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is delivering his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial. It is late August of 1963, but it could well have been late August of last year. Think of the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after white police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed black teenager Michael Brown, and hear King speak, 51 years earlier: “We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.”

Again and again. Peaceful protests after Brown was killed were monitored by a police force heavily armed with surplus military equipment. Eric Garner was choked to death on Staten Island in July; a friend recorded this on video, but the officer who killed him—using a banned technique—was not indicted.

In Ann Arbor, Michigan, on Nov. 9 of last year, police shot and killed Aura Rosser, claiming that she had confronted them with a knife when they came to investigate a domestic disturbance call.

In Cleveland, on Nov. 13, Tanisha Anderson died after police assaulted her. Her family had called the police to come calm her down during an argument.

On Nov. 22 in the same city, Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old boy, was shot and killed by police responding to a report of “a guy with a gun.” They then tackled his fourteen-year-old sister, handcuffed her, and put her in a squad car. When the children’s mother, Samaria Rice, arrived, police refused to let her go to either child and threatened to arrest her.

Again and again, across the country. When Yvette Smith answered the door in Bastrop, Texas, on Feb.16 of last year, she was shot twice by police responding to a 911 call from the house. She died of her injuries.

Pearlie Golden was 93 years old when a police officer shot and killed her at her Hearne, Texas, home on May, three months before the nationally recognized shooting of Michael Brown.

“We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality,” King said in 1963. It’s 2015 now. Change “Negro” to “African-American,” and that sentence could have been spoken today.

On Dec. 7, 2014, about 30 protesters interrupted the 31st annual Troy Victorian Stroll. Lying down in front of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument at the busy intersection of Broadway and 2nd Street, they chanted, “Black lives matter!” and “Silence is violence.” They handed out sheets of paper, each with the name and photograph of a different black person killed by police in the United States. Then they walked south on 2nd, chanting and holding signs in the bright winter sun.

I heard several people mutter angrily that they were disrupting the event and should just go away. And I saw one man with his daughter, who looked about five. “What does ‘Silence is violence’ mean?” she asked.

“It means if you see someone do something bad and you don’t tell anyone about it, then you’re just as bad as the person who did it,” he told her. She seemed satisfied with this, and he took her pink-mittened hand in his black-gloved one and they walked on.

It was a reductive explanation, but what could he say? What could anyone say?

All the people I heard disparage the protesters were white. That man and his daughter were black. It could have been coincidence. But the weight of American history says it’s not.

It’s 2015 now, but there are still states that celebrate Robert E. Lee’s birthday. There are still more than 100 active chapters of the Ku Klux Klan in dozens of states, including New York. The racist—and publicly accessible—message board site Stormfront proclaims, without irony, on its home page, “Every month is white history month.”

On January 6, the NAACP offices in Colorado Springs were bombed, and national news media didn’t pick up the story until a day later. The FBI has released a sketch of a person of interest, a balding white man in his forties.

Fifty years ago, on Dec. 10, 1964, King accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway. He was 35, the youngest person ever to receive the prize, and his acceptance speech is just as forcefully delivered as his “I Have a Dream” speech. In the video of his speech, the audience is almost entirely white, and they do not interject or clap or visibly react much until the end, when a rain of applause follows his words.

Like the “I Have a Dream” speech, this sermon from half a century ago resonates today. King alludes to horrific events that happened the day before he spoke, but even in the face of such violence, he continues to be optimistic: “I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality,” he says.

Listen to him: “I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. … I believe that even amid today’s mortar bursts and whining bullets, there is still hope for a brighter tomorrow.”

That idealism in the face of brutal reality, that determination despite violent opposition from individuals and the state, that optimism despite the long odds: that is King’s legacy. Listening to him, I felt an aching hope rise in my throat.